By Saura Louise Heinsen, Ayo Wahlberg, and Helle Vendel Petersen

https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2021.1893654

Abstract: Today, in the field of hereditary colorectal cancer in Denmark, more than 40,000 identified healthy individuals with an increased risk of cancer are enrolled in a surveillance program aimed at preventing cancer form developing, with numbers still growing. What this group of healthy individuals has in common is lifelong regular interaction with a healthcare system that has been traditionally geared towards treating the acutely and chronically ill. In this article, we explore how people living with an inherited elevated risk of colorectal cancer orient themselves towards their families’ and their own predispositions as well as the lifelong surveillance trajectories that they have embarked upon– what we call surveillance life. Unlike prior critiques of predictive genetic testing as generative of ‘pre-patients’ or ‘pre-symtomatically ill’, we suggest that for those enrolled in lifelong surveillance programs in welfare state Denmark, the relevance of risk fluctuates according to certain moments in the life, e.g. at family reunions, when a close relative falls ill, in the time leading up to a surveillance colonoscopy or when enduring the procedures themselves. As such, rather than characterizing surveillance life in therms of living with chronic risk, we show how ‘genetically at risk’ chronicities take shape as persons come to terms with a disease that possibly awaits them leading them to calibrate familial bonds and responsibilities while leading lives punctuated by regular medical checkups.

Surveillance based medical care is a program where people determined by either their current health or genetic testing to be at elevated risk of disease undergo repeated, additional medical testing in order to catch disease in its early stages. They may also make certain lifestyle choices in the hopes of preventing disease entirely. Surveillance medicine has many supporters and many critics– supporters argue that it saves lives, while critics argue that it manufactures epidemics where they do not exist and causes unnecessary anxiety in patients.

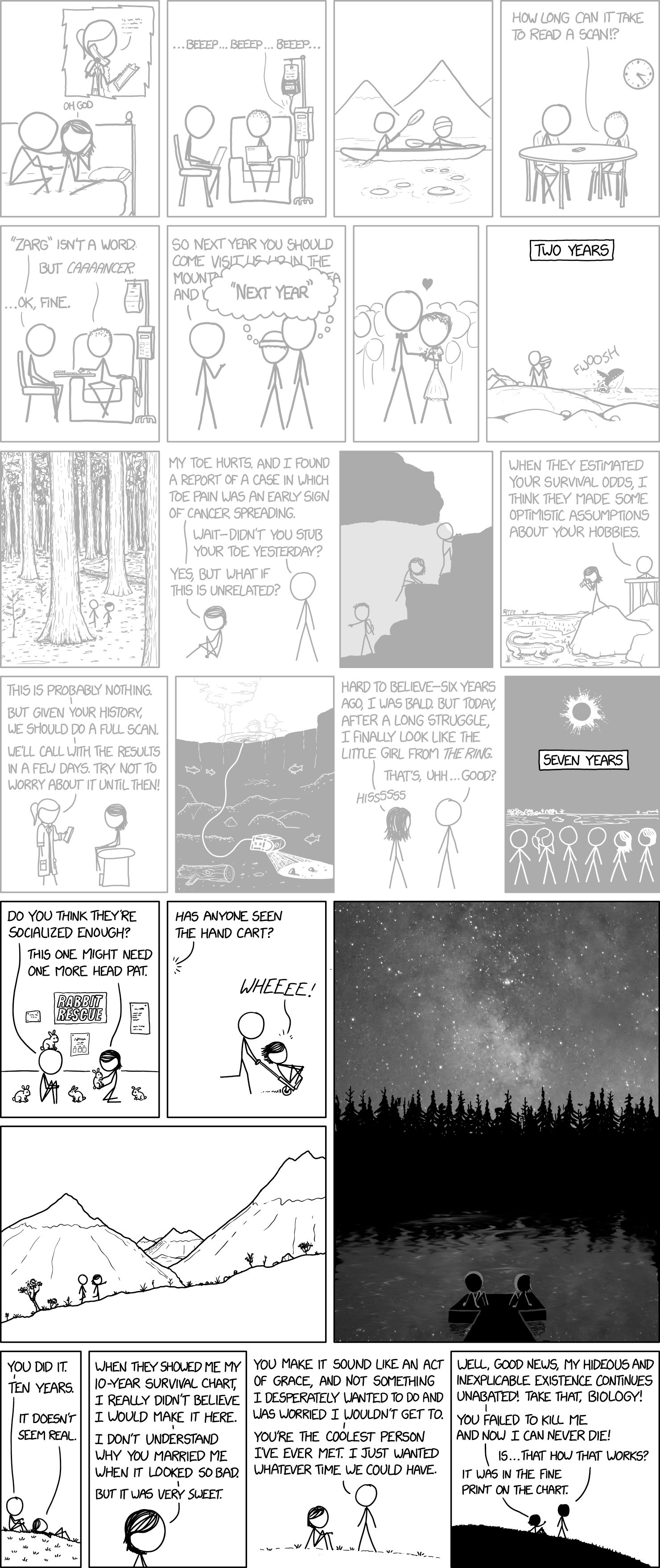

This paper in particular pushes back against a criticism of surveillance testing which holds that all patients who are determined to be at risk immediately consider themselves to be ill or are overcome with concern over bodily deterioration. Rather, it argues that medical attentiveness is only heightened at certain moments, which include both key life events and routine medical checkups. Furthermore, patients of surveillance medicine are operating on a fundamentally different motivation than those who are chronically ill. Rather than participating in repeat doctor’s visits in order to live good lives in spite of disease, they are participating to stay healthy and avoid disease.

I think this paper provides a helpful middle ground for both critics and supporters of surveillance medicine, as it both acknowledges that patients outlooks and perspectives change when they learn of their “risk status” but also provides some evidence that this shift is not always big or traumatic, and the delineation in motivations to seek care between people who are ill and those who are at risk is important to discuss.