By Sara Marie Hebsgaard Offerson, Mette Beck Risor, Peter Vedsted, and Rikke Sand Andersen

https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.5.5.540

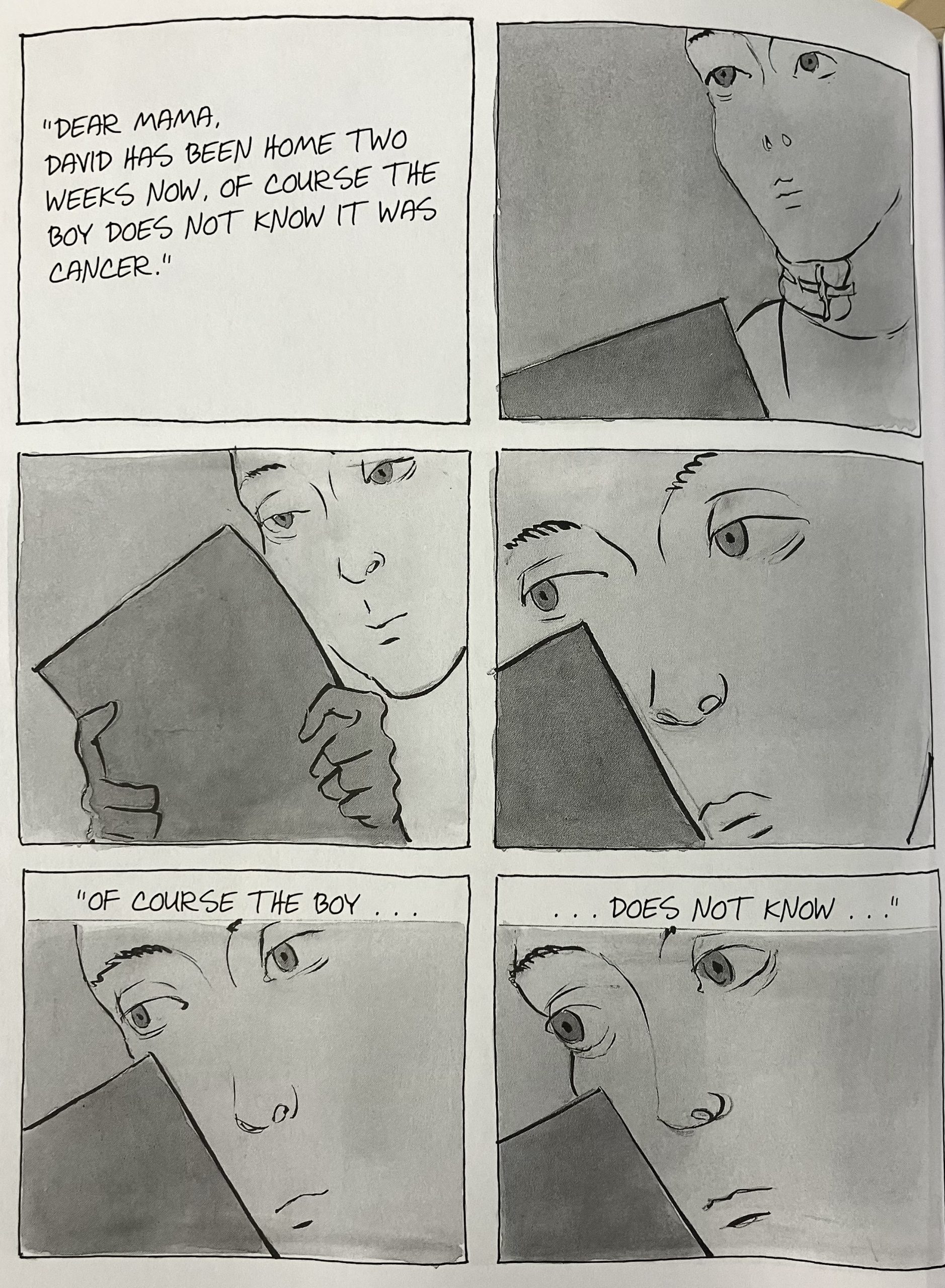

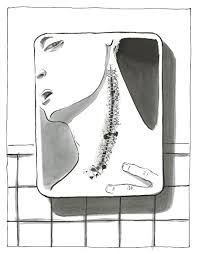

Abstract: Approaching the presence of cancer in everyday life in terms of mythologies, the article examines what cancer is and how cancer-related potentialities are enacted and embodied in the context of contemporary regimes of anticipation. Based on ethnographic fieldwork in a suburban Danish middle-class community among people who were not immediately afflicted by cancer, we describe different and paradoxical cancer mythologies and show how they provide multiple ways of understanding, anticipating, and dealing with cancer in everyday life. Special attention is paid to the relation between bio-medically informed notions of symptoms and bodily processes, and a ghostly and muted presence of caner, particularly when people are faced with more tangible cancer worries. we explore how contemporary cancer disease-control strategies emphasizing ‘symptom awareness’ interweave with and add to cancer mythologies. We suggest that these strategies also carry moral significance as directives (be aware of early signs of cancer and seek care in time) and create n unintended illusion of certainty that does not correspond with everyday embodied forms of uncertainty and ambiguity. We argue that paying attention to the continuous cultural configurations of cancer that exist “before cancer” will increase understanding of how the public health construction of “cancer awareness” relates to everyday health practices such as symptom experience and health care seeking.

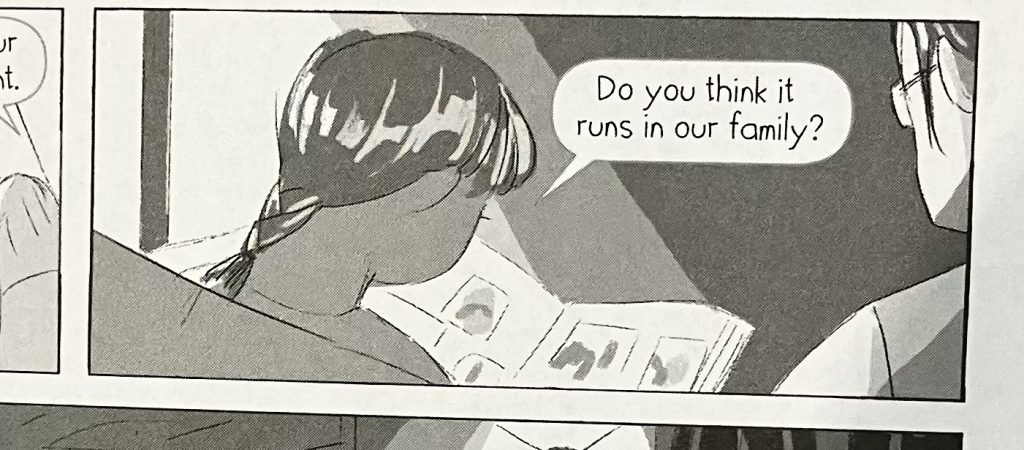

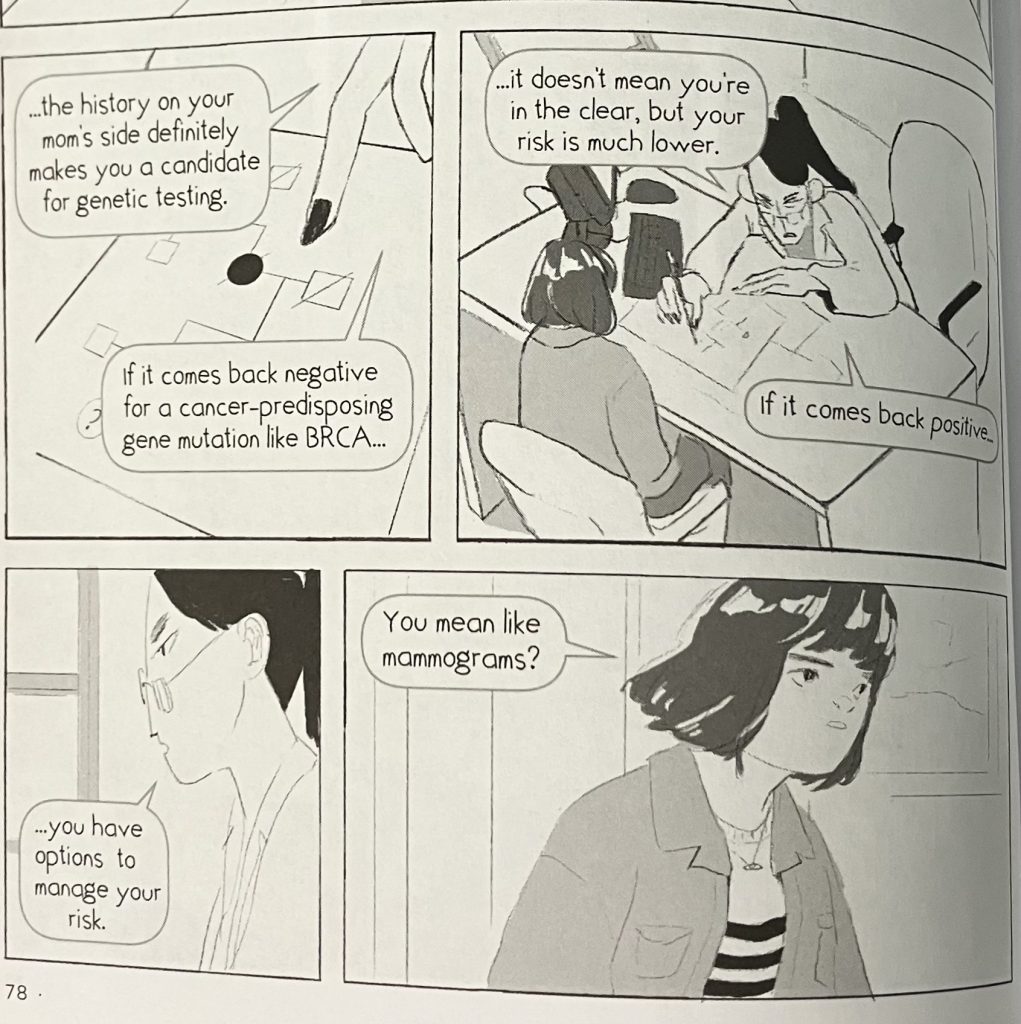

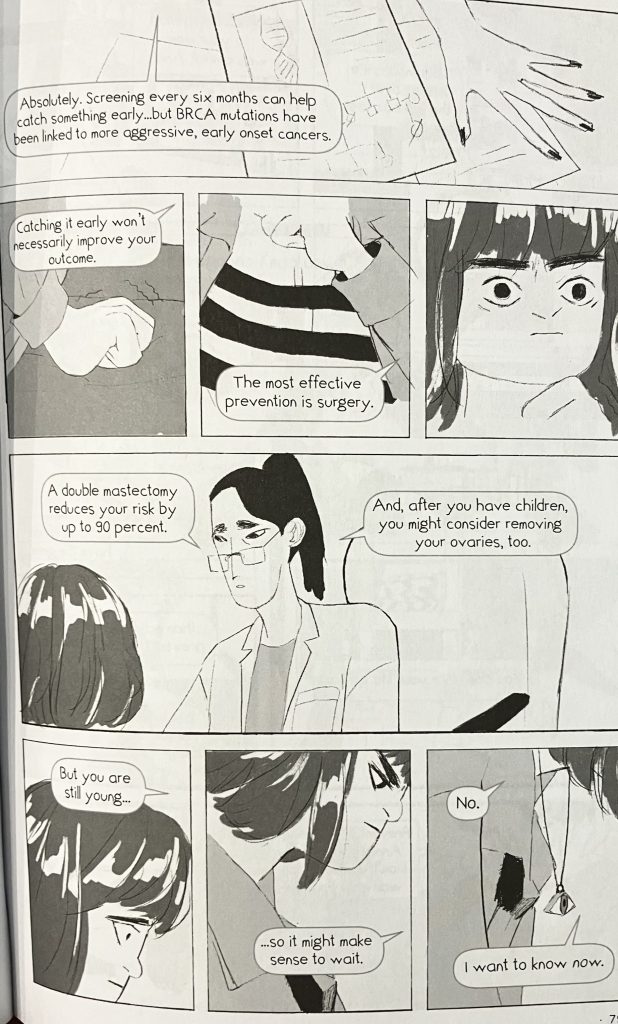

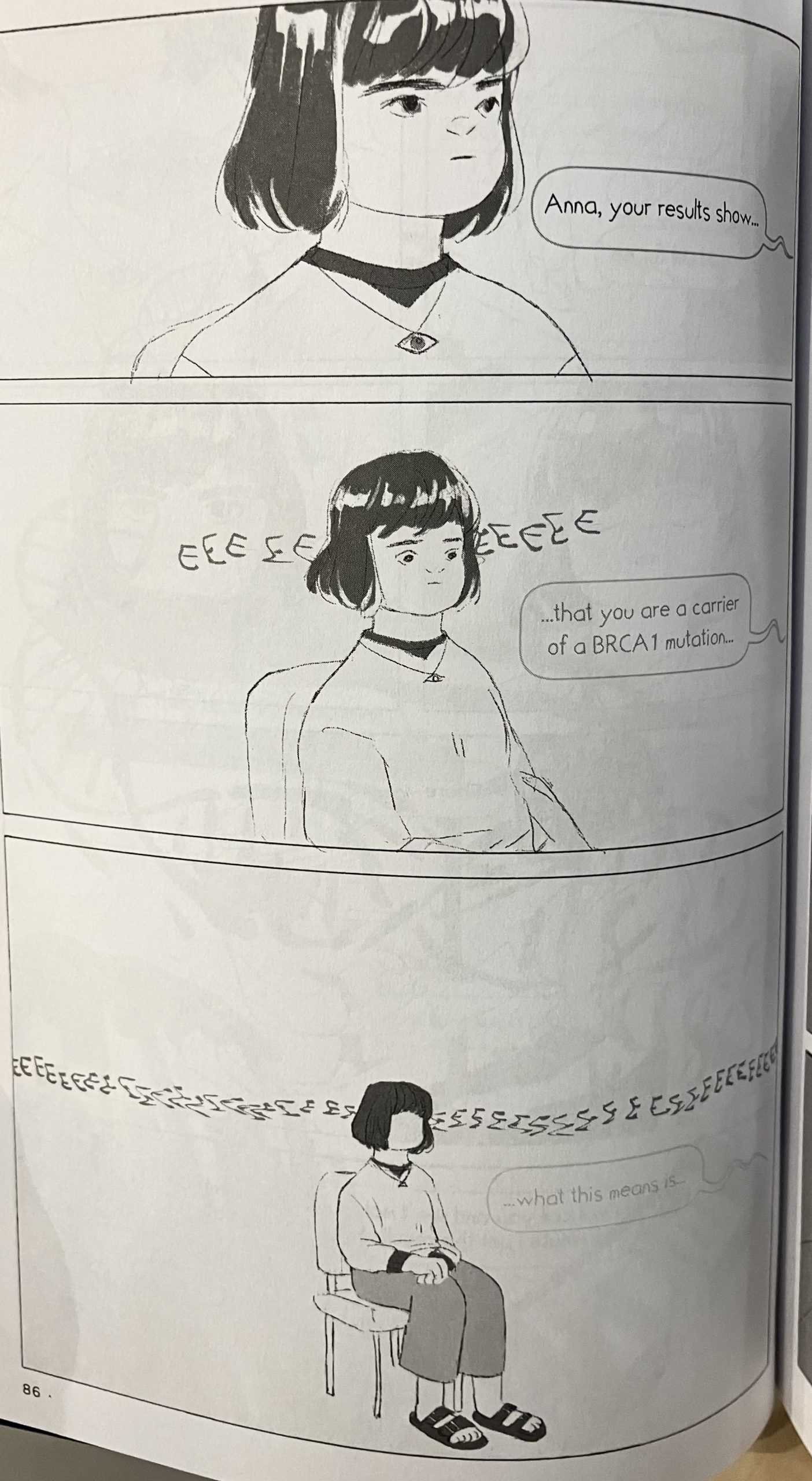

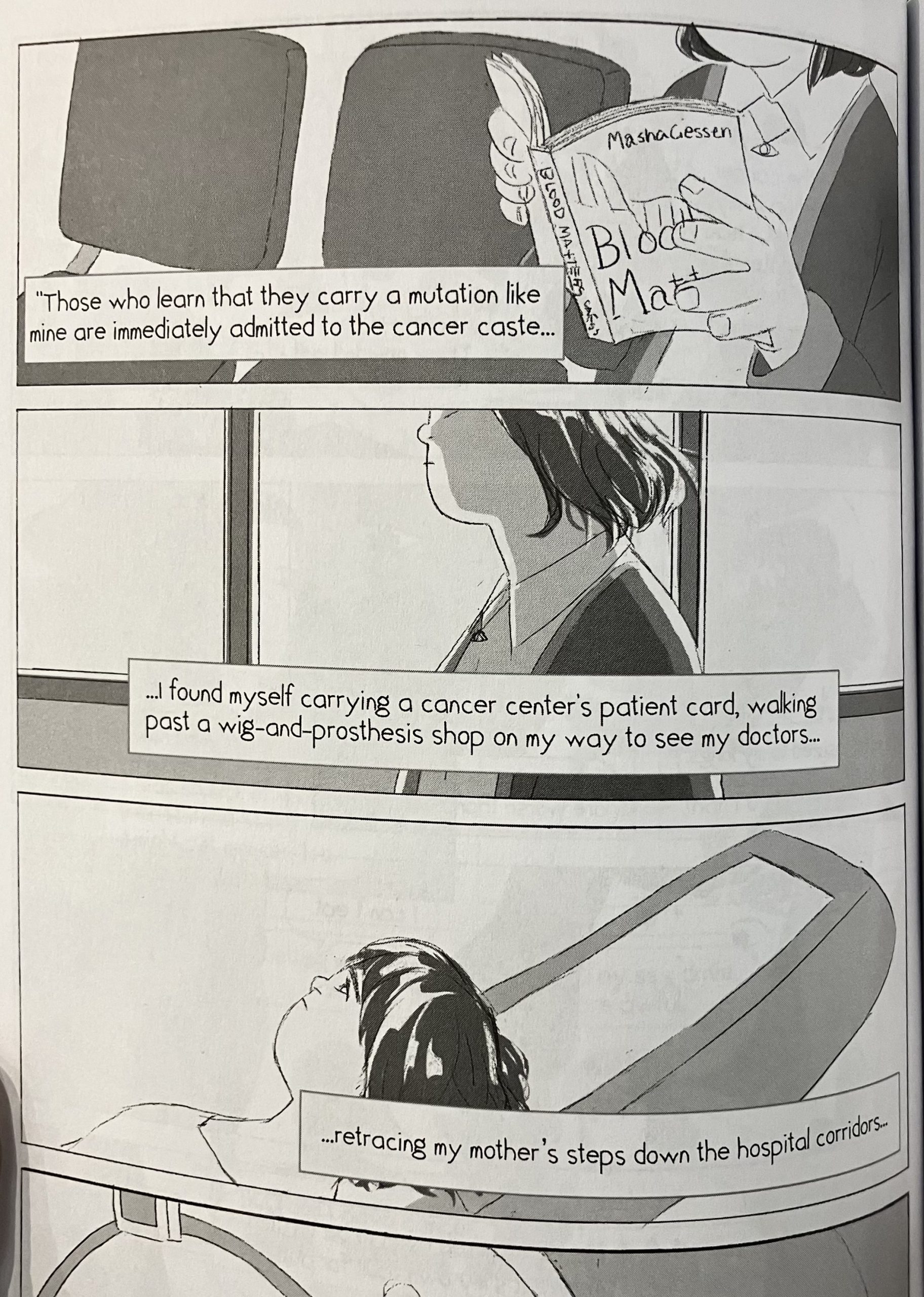

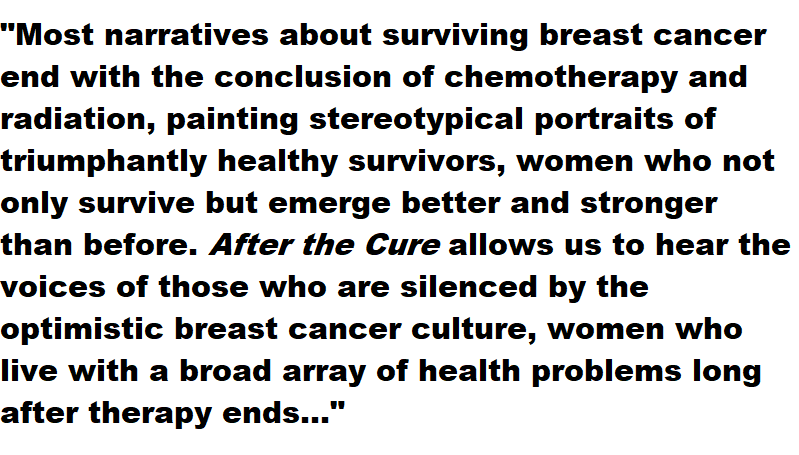

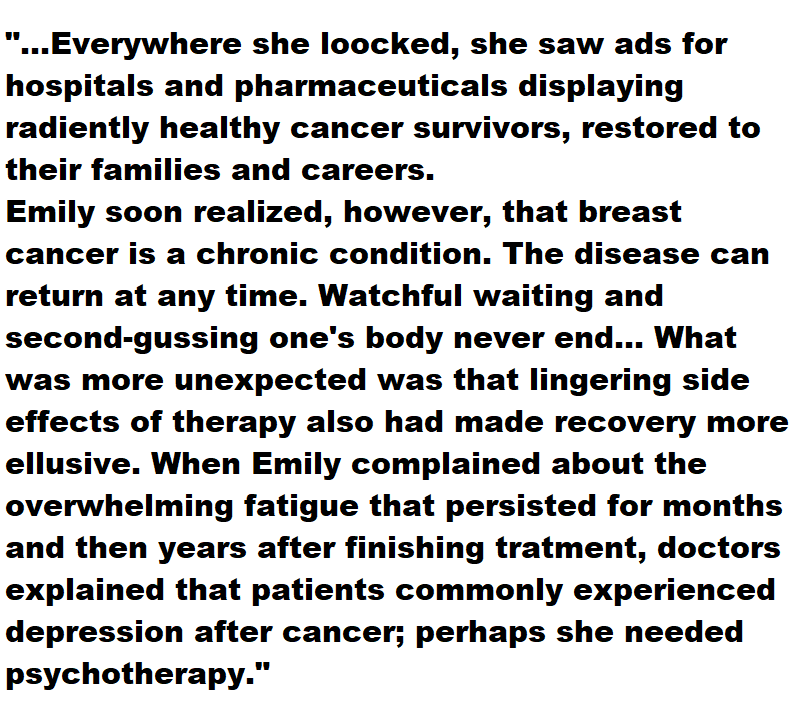

This article examines the ways in which public health messaging contributes to the mythologies of cancer.

This adds an interesting dimension to the question of anticipatory patienthood, a term which describes the ways in which people determined to be “at risk” of disease are constructed as patients even though they are still technically well, and are subject to particular expectations and chronicities. The article essentially argues that public health expands the umbrella of anticipatory patienthood to the general public, and this manifests in anxieties over certain behaviors and symptoms as potentially leading to cancer. Public health messaging also reinforces particular narratives about cancer, leading to a perception of certainty which does not reflect the reality of the illness.